The Mallee: A History

Statement

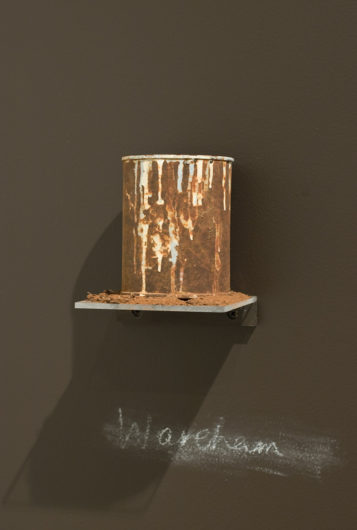

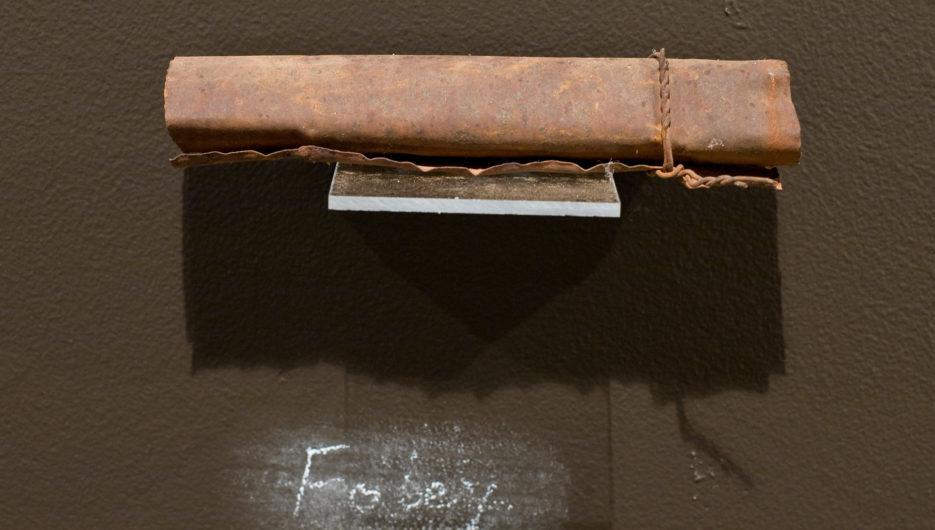

In various exhibitions in 2000, 2009/10 and 2011, The Mallee: a history, was installed in varying arrangements, 200 odd rusty brown tin cans, of endless size, shape, content and condition, which are juxtaposed on transparent perpex shelves a 15 metre painted, earth wall.

Underneath each can is written the selected surname of a farmer who has at one time occupied this Mallee land in North West Victoria.The words faintly written and systematically erased, then re-written in white chalk, are half buried like the inscriptions on a gravestone. In grid formation, like the view of farming properties from the air, this wall is a commemoration, a memorialisation to individual and collective ambition and persistence.

These long abandoned tin cans were collected from the informal dumps located on the farming properties. It is apparent to me that these disposed objects have rich potential in forming associations with the now vanished people that once used them. They could, as Hal Foster noted, make historical information often lost or displaced, physically present. I was reinforced by the evidence that, material traces of people are everywhere, object-presences which conjure up the absence of those who wore, wielded, utilised, and consumed them.

The tin can is a humble, but important utilitarian object survives the ravages of ruination better than most objects. Despite the long vanished, ephemeral labelling and other commercial branding contrivances, the tin cans themselves are resolute. With a warm, generic patina of powdered rust, they homogenise with the burnt Malllee earth, as if by some grand hegemonic design. In an exhibition review, curator and artist, Ian Hamilton wrote of, both textured and monochromatic, they speak of breakdown, not just of metal, but of life itself.

Of course the tin can is an important and persuasive object. Patented in 1810 by British merchant, Peter Durand, it changed food preservation all around the world, providing readymade, hermetically sealed food for armies in battle, exploration to un-explored terrain, and of course for isolated farmers. The irony of primary food producers in inland Australia surviving on the canned herrings, kippers and sardines from Scandinavia, is itself a persuasive symbol of temporality.

Categorised in: All works, In footer

This post was written by Alex Fettling